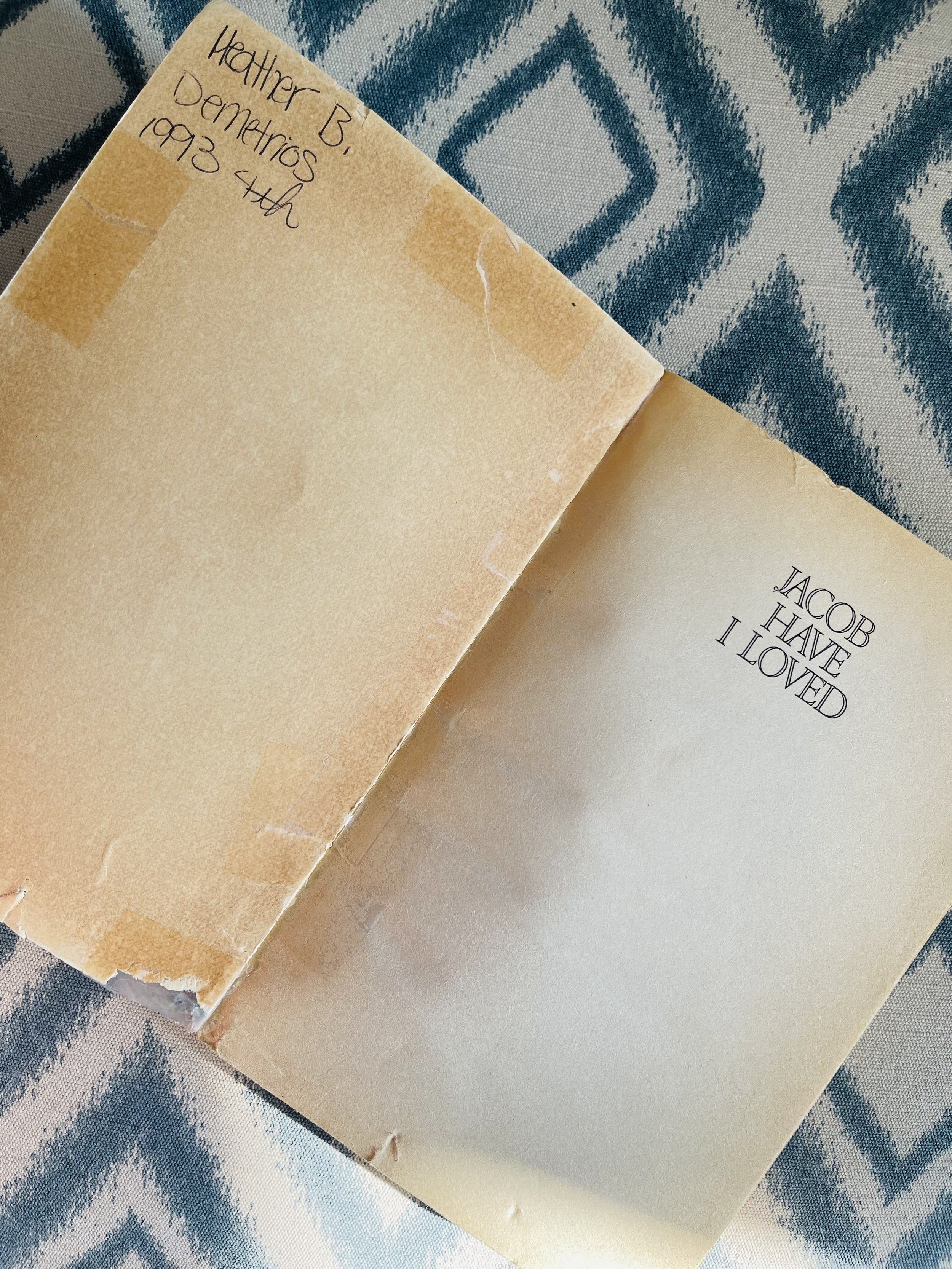

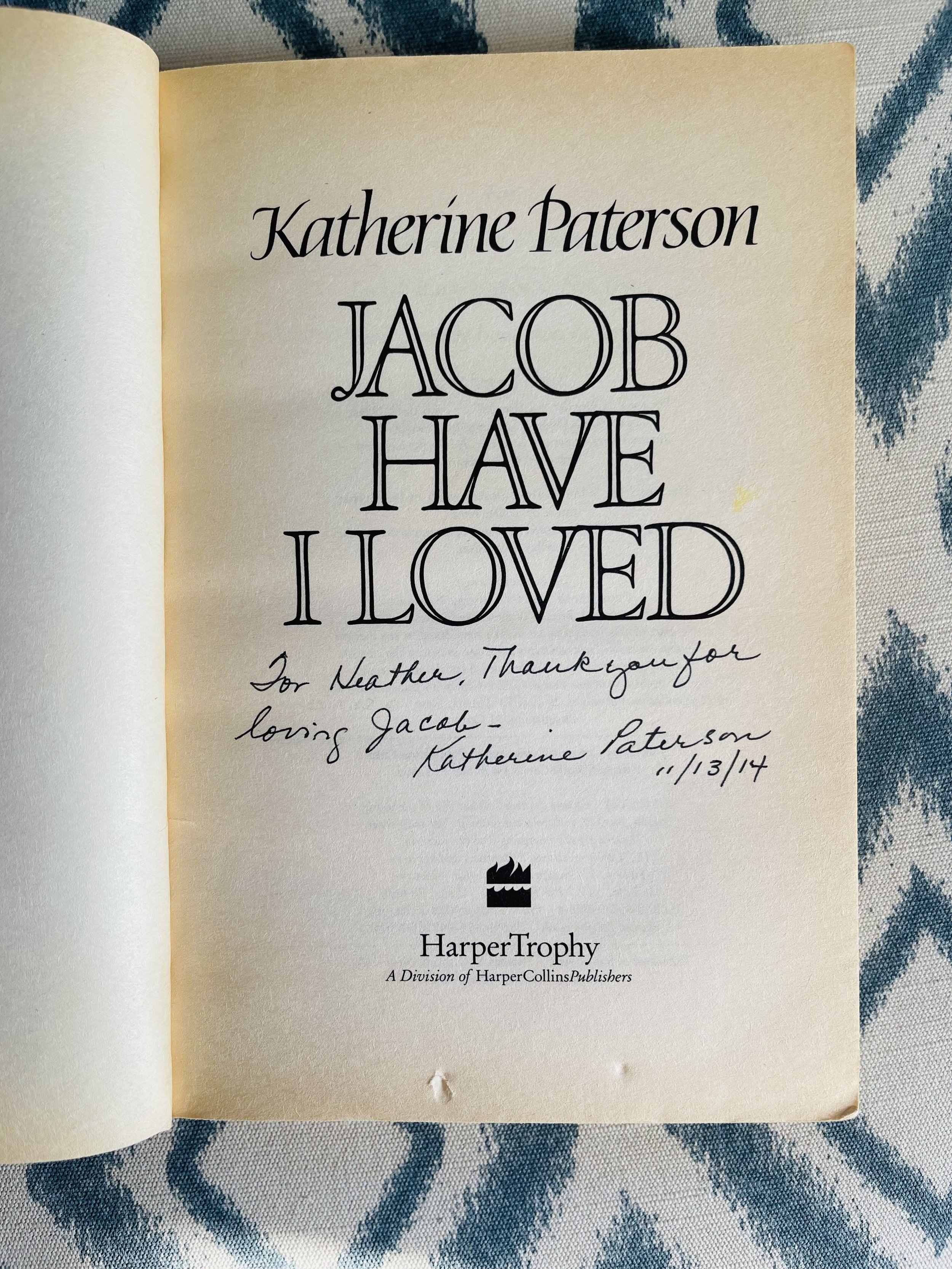

Excerpt from first draft of A Correspondence

by Heather Demetrios Fehst, all rights reserved

.........................................................................................................

It took me a long time to realize that I could say something with my camera. I wasn’t great with words, not for years and years, so you can imagine my relief when I realized that it was possible to communicate without using a single one.

When you’re a missionaries’ kid, you’re perpetually on the outside. I used to think that language is the number one barrier to real connection with others, and it was true for me then. But after years of forging relationships with people around the world where no one spoke my language, I know differently now. I’ve spent entire evenings with women in the Middle East and North Africa, connecting over tea and babies and other shared delights without ever understanding a word they said.

I’ve ridden on the backs of motorbikes in shared ecstasy over a blazing sunset with drivers who spoke in smiles and laughter. And I’ve run for my life with men who would never be able to pronounce my name, but could scream in my language just fine. This was real connection, more true and lasting to me than any Brooklyn dinner party or failed first date.

But as a kid, I didn’t want to connect. I’d been conscripted into the Lord’s service, an unwilling member of a band of Americans who passed out tracts in languages we were only decently proficient in. (My father once attempted to talk about Bonhoeffer with a young Russian Orthodox priest and it didn’t go well). I resented my outsiderness and my parents. I wanted to be in Boston, with my grandma and Mike’s cannolis and Feline’s Basement. I wanted to be “normal,” which I thought was a thing that actually existed, but now know differently.

I was just five when my parents moved us from Moscow to plant a church in Simferopol, a large city in the Crimean peninsula, later annexed by Russia. This was long before most people in the US knew there was a place called the Crimea to begin with.

I had a bewildering relationship to the city and my place in it. Even as a young child, I wanted to hate it, but it kept creeping into the cracks in my heart, the kind of light that’s more beautiful because of the shadows surrounding it. My favorite kind of light to shoot.

I thrilled over buying little jars of fresh sour cream at the markets from babushkas with faded kerchiefs wrapped around their heads, riding the rickety trolleys past faded peach plaster buildings adorned in the crumbling old world glory of post-soviet Europe, greeting the bread lady who banged on our metal gate with a stick each morning—I’d hand over a few kopeks in exchange for that quintessentially slavic bread, rich and dark, which I’d smother in fresh butter or a spoonful of the precious Jif peanut butter my grandma would send a few times a year.

I enjoyed speaking Russian and Ukrainian and found I was quite good at it. There were trips to the Black Sea, where we’d sunbathe on the black sands of Yalta. Eating special dinners out in one of Simferopol’s many Tatar restaurants, where we’d sit at low tables and gorge on meat pies and fried fish. I worked hard to elicit those genuine smiles from a population schooled in never taking off the armor of Soviet gruffness—good training, as it turns out, for my work as a photographer.

My tutors were kind and I eventually made friends—Ukrainian kids whose parents went to our church. We bonded over marathons of Slap Jack, my American hands slapping against their Ukrainian ones as we tried to increase our individual piles of cards. We watched movies my grandma sent from America and, as we all slipped over the edge from childhood into adolescence, we traded the bootleg CDs you could buy in the subway station for the equivalent of an American dollar—music was another way to connect, I’d find, without speaking the same language.

Around the time my chest began to fill out and the awkward lines of my body soften into an approximation of what it is today, I fell into a hormone-induced love with the man my parents had employed as their fixer in the region—Dima was a local journalist, a decade older than me and the object of my adoration and fascination. In a way, my unrequited love for Dima is what led to the actual love of my life: photography.

When people ask me why or how I became a photographer, I tell them about the old violinist in the Kyiv subway station that I heard play the summer I turned seventeen. I was heartbroken because my parents, wary of any lines being crossed, had forbidden me from spending any time alone with Dima. My father had insisted on taking me with him to Kyiv on a meeting he had with another family stationed in the Ukraine and I was being very sullen about the whole thing.

I’d discovered that he talked to me less when the old Canon a volunteer from the States had gifted me was against my face, so I was taking a lot of photographs. This was before digital—it was all on film, so I didn’t press the shutter too often. This gave me time to line up shots, to teach myself how to find alignment with the horizontal and vertical lines in my environment. To figure out what was interesting to me. I played with light, discovered texture and depth. Began to notice details. Contrasts. Most of all, I loved that with a camera between me and the world, I was allowed to stare at people and it wasn’t considered rude.

We were in one of the lively subterranean markets that filled the Kyiv subway station tunnels when I heard the violin—a lonesome Rachmaninoff refrain echoing off the dirty tiles and slipping past the stands filled with pirated movies and music from America, sliding around the pelmeni ladies who sold the dumplings in little plastic baggies.

I followed the music, to where an old man who looked like a cross between Rasputin and Tolstoy stood before a filthy wall where several faded Soviet-era concert posters had been lovingly pasted against the tile. He played with his eyes closed, the deep lines of his face filled with a youthful rapture, a lightness that took hold of his frame and gave it a momentary respite from old age and patched coats.

My eyes caught on the posters behind him—the face in the black and white photographs was much younger, but I recognized that transcendent smile. He’d been a soloist—and a popular one at that. Today his concert hall was Arsenalna station, deep beneath the Dnieper. Instead of an orchestra pit, he played behind an open case that held a few kopeks.

It was the first time my body told me to shoot—as though the image itself had the ability to reach between my ribs, grab my heart, and give it a good, no-nonsense twist.

The man, the posters, the case, the station—it was the whole of the Ukraine for me. The Soviet past and my present had become entangled in a single moment, a single image that that his violin scored and my camera wanted to capture and hold forever, a pinned butterfly.

I took a breath and raised the camera to my eye.

Eight years after my brother’s death in Afghanistan, my subway Rachmaninoff would lead me to a platoon of Marines in the mountains of Kandahar province, photographing them as they fought on what would become the deadliest day of that nearly endless war—and my first combat embed.